Don’t make the mistake of marrying the best possible husband, any more than you would make the mistake of buying the best possible car. They’re both likely to cost more than they’re worth to you.

Your ideal mate is probably close to ideal for a lot of other people, too. That means you’ll have to make concessions to win him and concessions to keep him — on every issue from how many children you’ll have to who’s cooking dinner tonight. A perfect husband is a costly extravagance. Most costly extravagances turn out to be mistakes.

–Advice intended by economist Steven E. Landsburg for his then nine year-old daughter.*

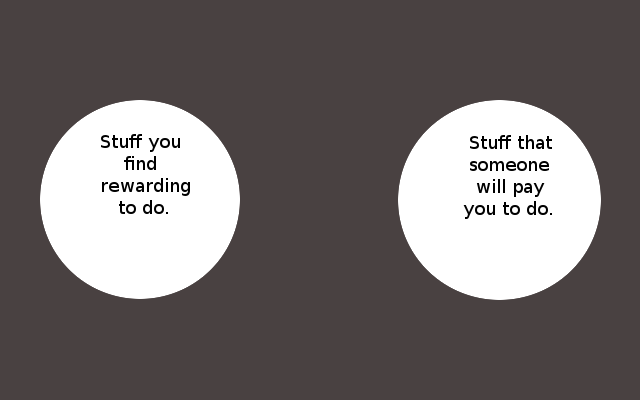

In Diderot’s Jacques le fataliste et son maître the eponymous Master observes “Tous les jours on couche avec des femmes qu’on n’aime pas, et l’on ne couche pas avec des femmes qu’on aime.” I observe that every day people get up and spend most of their waking hours doing what they do not love and not doing what they do love. The following Venn diagram illustrates an explanation for my observation which I believe will apply to most if not all people.

Think of the things you find rewarding to do. For me it likely means intellectual work — the life of a humanistic scholar and teacher, or pure scientist or pure mathematician. For others it might be a life of artistic achievement, as a writer, poet, musician, actor, dancer, whatever. For still others differently constituted it might involve rearing (their own) children or helping the less fortunate. All of these activities are richly rewarding for most of those engaged in them. They’re “meaningful.” Another thing they have in common is that if you devote yourself to any of them your expected lifetime monetary compensation will be shit. To be sure, in some of these activities there will be a handful of superstars — there will be some musicians like this — who command big returns. These superstars are the equivalent of lottery winners in their respective professions. As we’ve noted before, playing the lottery is not a rational life strategy. In some others like science and scholarship there are some opportunities for a barely middle-class existence, but very few relative to the number of aspirants and such opportunities as there are will be controlled by unpleasant gatekeepers who use them to enhance their own status and opportunities — most of academic hiring is like this. And in others you can pretty much just expect to starve. No one is going to pay you to rear your own children, and almost no one is going to pay even the next Byron to write poetry.

The reason that “meaningful” work is on average so poorly paid as at base the same reason outlined by Professor Landesburg as to why having a perfect spouse is a bad idea. If the work is meaningful to you, then it is highly likely to be meaningful to many, many other people. All the would-be writers, or scientists, or musicians trying to pile in drive down expected compensation to some socially-determined level of subsistence, or perhaps even lower than that.

Only the jobs that suck — ranging from that of the lowest man on the garbage collection crew to that of the slickest attorney fiddling the rules to allow her billionaire clients to pay less in taxes than their servants — are going to pay much to the non-winners in life’s lottery. People with work that needs doing can’t (yet, anyway) just enslave people who can do the work, and so some inducement, usually monetary, will have to be offered to overcome the general sense of weary disgust such work induces.

So if you’re like most people, your life will consist of an ugly choice. Try to do something you love and be poor or do something you do not love and be, well, if not exactly rich than at not poor, or at least less poor. Romantics will tell you to do what you love. But beware! Being poor, at least in a society like the contemporary United States does, not just mean having fewer things than other people. It means being exposed to the contempt and abuse of the rest of money-worshiping society, and having little recourse against such when it happens to you. It also means that even the simplest parts of life will be exhausting — try living without your own car in most parts of the country and see how that works out for you. Sticking with what you love is likely to be a very costly extravagance indeed.

Of course, doing what will make you not so poor is not picnic, either. It means coming home tired every evening and, if you are not good at self-deception, not good at forcing ugly inconvenient facts out of your mind, a follower of the bitter path of hard-nosed realism, you will realize that the spent state in which you are spending your evening will repeat itself over and over again, hundreds and thousands of times, down years and decades until it ceases only in your becoming a corpse, whether a traditional one rotting in the ground or a living one rotting in one of the facilities in which we warehouse our elderly will scarcely seem to matter.

That’s the choice most of you will face.

And if you have children, that’s the choice most of them will have thrust upon them, thanks to you.

***Note***

*[I stupidly forgot to put in this note when I first wrote the post, and am correcting that now.] See Steven E. Landsburg, Fair Play: What Your Child Can Teach You About Economics, Values, and the Meaning of Life. (New York: Free Press, 1997), pp. 216-7. Back to main text.