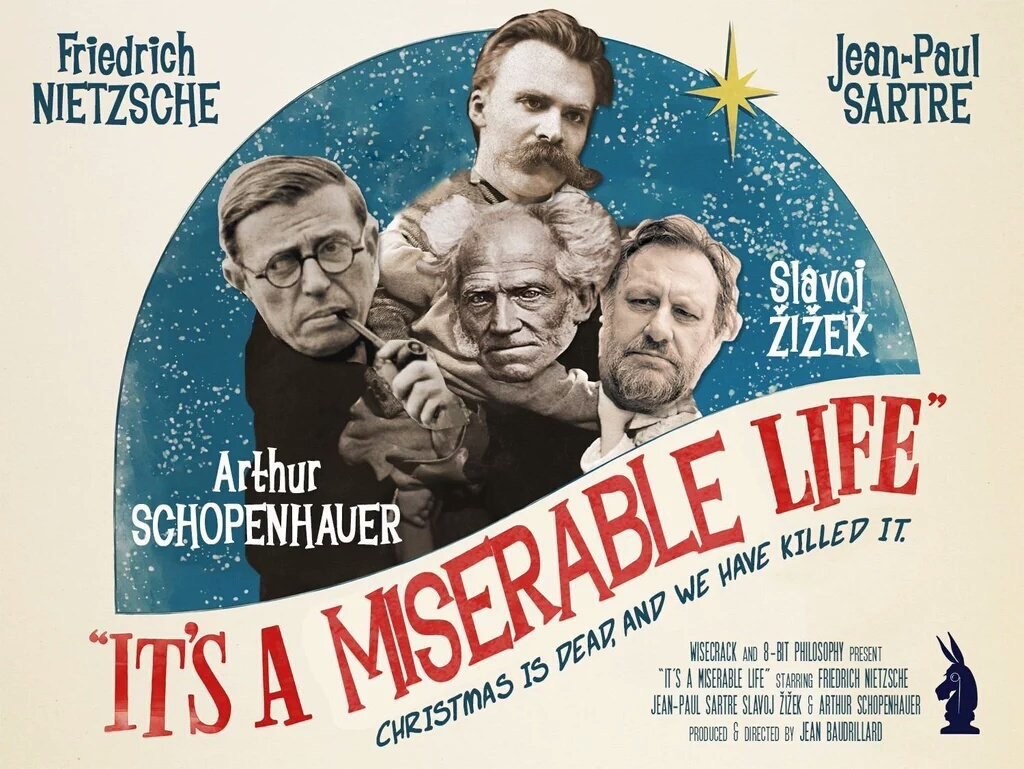

What does the future really bring? What can we expect in 2085 or 2115? Beginning back in the nineteenth century people like Karl Marx thought that the future was socialism. With a bit more experience and perhaps more wisdom Rosa Luxemburg would modify this prediction and add a bit of contingency. We faced, she thought, a choice between socialism and barbarism. Further along in history we can modify this still further and drop socialism altogether from the picture. Our future is just barbarism.

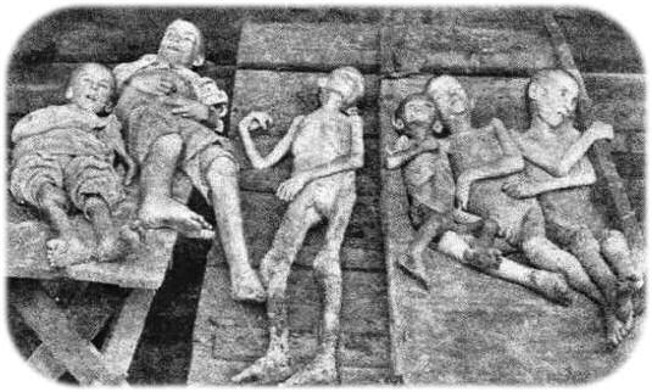

Projecting from what we can see all around us, we can imagine two things happening: (1) most of the ways in which people have traditionally earned a living will vanish, as machines get ever cleverer and more capable and (2) wealth will be concentrated in ever-fewer hands. Public policy could change (2), but I’m not counting on that. The rich can generally buy the public policy they want, and you can bet the ones they will be buying will be place few impediments on, and indeed will mostly actively facilitate, their ever-continuing economic ascendancy. (And failing that, they can always follow the sage policy proposed by Jay Gould and hire one half of the (formerly) working class to kill the other half.) My bet on the world at the end of this century will be something like this: most wealth will be owned by a tiny minority of people. Not the “one percent.” More like the one percent of the one percent. Most other people will be quite poor and live nasty, brutish, and short lives of insecurity in a large proletariat.1 Given the likely environmental devastations of the next century and the rending of our now-tatty social contract by heightened inequality, its existence will probably be considerably more miserable than that of impoverished first-worlders today. Compared with the lives that most people will live a century from now, those of street-level characters from The Wire will appear to be from a lost golden age of peace and prosperity.

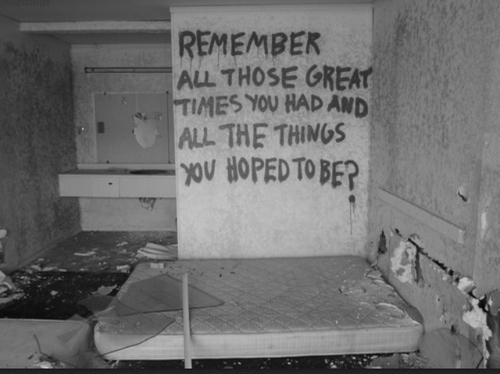

Between the tiny group of the rich and the vast proletariat there will be a small, insecure, and very frightened group of people in a sort of middle class. These people will be the “one percent” of the world. Who will they be? Those who strain muscle and nerve so that the lives of the truly rich might be as pleasant as possible: artisans, performers, valets, personal assistants, butlers, waiters, chefs, nannies, concierge physicians and nurses, teachers, dog-walkers, officer-class members of the security services, high-end sex-workers and the like. Life in the little middle class of this future will be more physically comfortable than that of the proletariat, but it will still be morally miserable — striving and conformist to an extent for exceeding that even of the middle classes of today. (And make no mistake, the middle class of today is miserable, in that your typical middle-class person is a corporate employee who is very frightened of having the wrong associates or saying the wrong thing on social media that will cause him or her to lose his or her job and sliding down the social ladder. You may to an extent enjoy freedom of speech with respect to what the government does to you, but certainly not to what your boss does to you.) Everything will be pervaded by the fear of failing to please their overclass masters and of slipping down a rank. Dissent, eccentricity, even individuality will be rapidly smothered. The threat of being exiled into the vast pool of misery that is the proletariat will hang over everything. Indeed, the existence of such a social place of misery will be one of the core functions of the proletariat — it will be a more effective deterrent of unpleasing-to-the-rich behavior than fines or prisons ever were. (The other function of the proletariat will be as a mutation pool to throw up occasional unusually pretty people or unusually talented people who can be recruited for the use of the rich, and also a source of conveniently-brutalized people who will make effective soldiers and security people.) The talents of the middle class, such as they are, will be in providing personal services to the rich. While they do so, they will live in a prison — a prison without walls, but a very effective prison nonetheless.

One might object in a world of very clever machines that the rich could or would do away with the services of human beings altogether. This is no so. Human servitors will be needed and desired (1) in spite of advances in computers and robotics and so on, there will likely remain certain services which human beings perform better than others and (2) being directly served by other human beings is pleasurable and a mark of high status — indeed, is pleasurable precisely because it is a mark of high status. It is this second point that that is the more interesting and requires emphasis, so consider: what is classier: live theater or television? Being served by a human waiter or the automat? Getting a diagnosis from a computer or from a physician who makes house calls? Learning something from software or from hearing a lecture in an ivy-covered building by a tweed-coated professor? I’d predict that even if engineers succeed in producing very high-end sexbots those who can afford them will prefer the services of traditional made-of-flesh sex workers.

Writing about social status and consumption all the way back in 1982, Paul Fussell perspicaciously noted the existence of something he called the “organic materials principle.” Fussell is here talking principally about the clothes that rich people wore at the time he was writing, but the principle he detected generalizes.

…materials are classier the more they consist of anything that was once alive. That means wool, leather, silk, cotton, and fur. Only. All synthetic fibers are prole, partly because they’re cheaper than natural ones, partly because they’re not archaic, and partly because they’re uniform and hence boring — you’ll never find a bit of straw or sheep excrement woven into an acrylic sweater. Veblen got the point in 1899, speaking of mass-produced goods in general: “Machine-made goods of daily use are often admired and preferred precisely on account of their excessive perfection on the part of the vulgar and the underbred, who have not given thought to the punctilios of elegant consumption.” (The organic principle also determines that in kitchens wood is classier than Formica, and on the kitchen table a cotton cloth “higher” than plastic or oilcloth.)2

Classy things are made out of that which was once alive. And classy services are rendered by beings that are alive (even if they don’t have much-enviable lives). Thus the organic-materials principle crosses from the realm of that which is dead to that which is living. That people are a lot more expensive and perhaps a bit less precise than robots is not a bug in the system but one of its most desirable features.

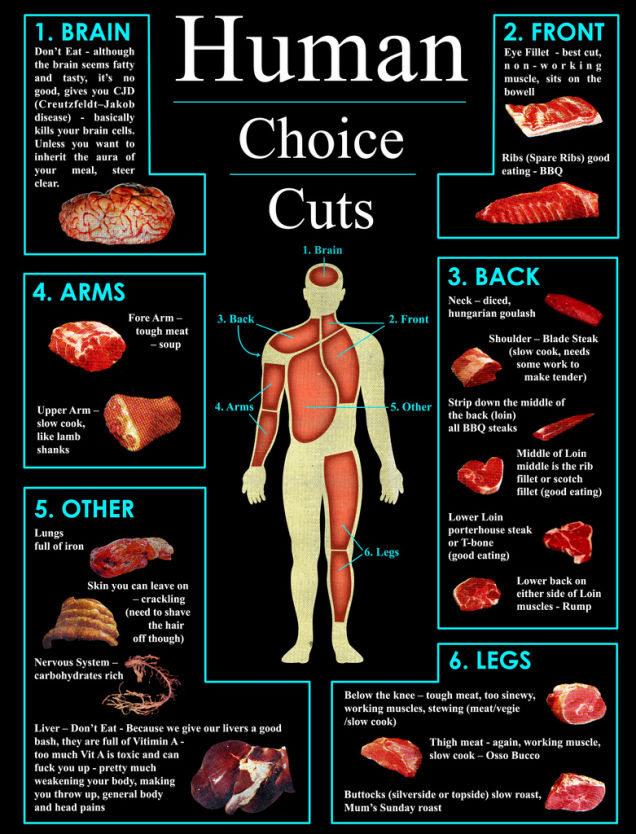

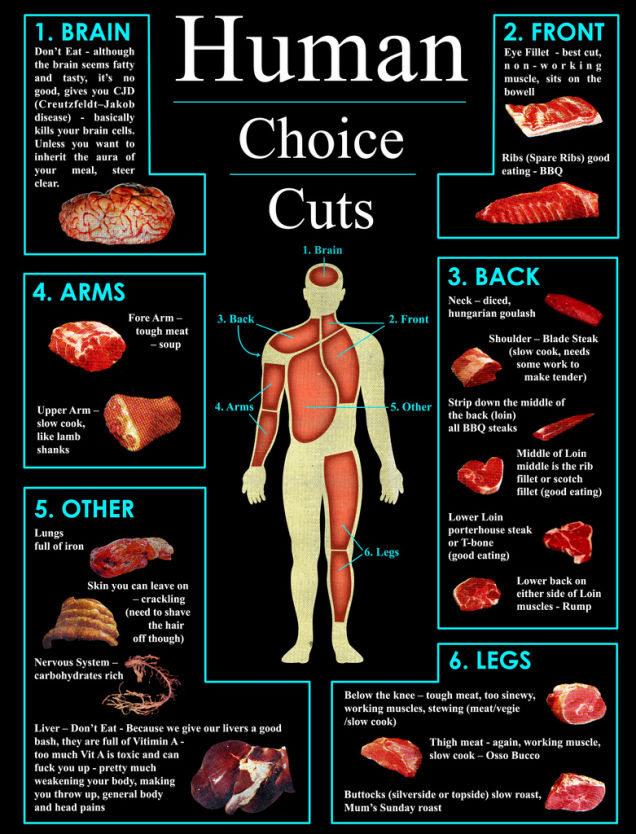

I would predict therefore that for the very rich meat-eating will continue as a practice (save among those who adopt vegetarianism as a boutique lifestyle choice), even though it seems fairly likely that we will soon be able to make tasty synthetic meat. Husbanding actual animals that will then be slaughtered and rendered into food (doubtless by an “artisanal”3 human butcher) will be expensive relative to a uniform product quietly grown in industrial vats, But the expense will be a feature, not a bug, a way of showing to the world your high status and wealth. The fact that it inflicts suffering on innocent animals might also be seen as a feature and not a bug. For is it not a sign of your power and status that you can snuff out humanitarian sentiment and eat what your wealth will permit you to eat? Continuing this line of thought, we might perhaps expect in certain quarters among the hyper-rich of the future to see the re-emergence of cannibalism as a hot culinary trend. For if it’s a sign of high status to be able to turn non-human animals into your food, and likewise a sign of high status to be able to use human beings to perform services for you, then the ability to turn human beings into tasty dishes would surely be high status squared, no? Perhaps the rich will hunt their meat down out of the proletariat. Or perhaps they will go for something higher status still, with purpose-raised human meat from special farms, perhaps something like the boarding schools for organ donors in Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go (the Kobe Beef of human meat!).

Click here for helpful tips and at least one tasty recipe. Honest!

All the miserable people in this future, the proles and the prisoners and the meat, who will they be if not the descendants of people living today? But there is of course a way in which we can save people from this fate, which is not to have any descendants. It would seem the only decent thing to do. Think about it: If you saw some great black train about to depart for a prison camp, or a howling wilderness, an abattoir for people, would you grab an innocent person, shove her onto the train, and lock the door behind her? You wouldn’t, you say? Then why would you have children? After all, the black train is there, setting off not across space, but through time to our future. If you have children, you’re shoving them (or their children) onto that train.

Happy Thanksgiving, everyone.

Notes

1“Proletariat” here might best be taken in the Roman rather than the Marxist sense, as this particular proletariat would consist of impoverished people who have no hope of carrying out the historical mission with which Marx charged them. It is perhaps interesting to note that by etymology “proletariat” means something like “those who produce offspring,” which would be exactly their role in this future dystopia. Back to main text.

2Paul Fussell, Class: A Guide through the American Status System. (New York, Simon & Schuster, 1982), p. 55. Back to main text.

3I wish I could remember who said it but can’t, that the real meaning of this hideous ad-man’s word “artisanal” which we now see pasted on so many things means “something that used to be made by working-class people and is now made by middle-class people. Back to main text.