Many people’s sense of meaning comes from history, especially the received history of their own country. They reflect on past events (as they understand them) and see them as a kind of glorious path. The fact that they are “part” of these events somehow by virtue of being part of that nation the history of which it is makes them feel a certain kind of pride and forms part of their belief that their lives have meaning.

American Patriotism, World ד Version

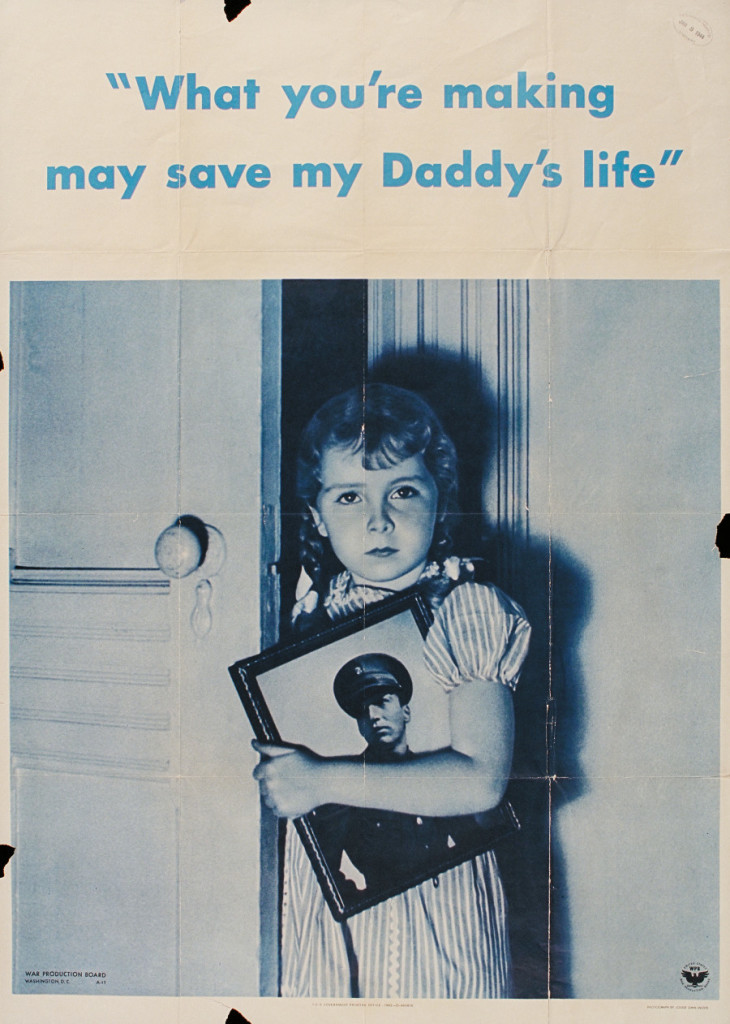

That’s abstract: here’s a more concrete example. I live in the United States of America, and I am surrounded by Americans, all but a very few of whom believe that their country “won” a big horrible historical event called the Second World War. The war was a war against “evil,” and a large part of it was against a particularly evil country called Nazi Germany run by a a particularly evil man named Adolf Hitler and his band of henchmen whose names were, well, something. This particularly evil country murdered and enslaved millions of innocent people — in particular millions of innocent Jews — but thanks to General Patton and D-Day and the Band of Brothers who we saw an HBO miniseries about and all that Hitler and his evil country were all defeated and the innocent people of Europe were saved. America went to war to save innocent people and democracy. A more reflective kind of American will note that while the war involved a great deal of suffering and destruction, after the war American, through something called the Marshall Plan, generously helped to rebuild Europe, including even its defeated former enemy, thus beginning an era of unprecedented peace and prosperity.

These are things that probably most Americans believe, roughly. Purely as matters of historical interpretation, there’s plenty to criticize about them. The United States quietly observed rising Nazi persecutions of German Jews for years without doing very much about it, declining generally even to raise immigration quotas to give increasingly threatened European Jews anywhere to flee to. American participation in the European war began not when the United States declared war on Germany but vice versa, and the enterprise of “saving innocent Europeans” played nothing except for a rhetorical role in the justification of America’s role in the war. (And “saving European Jews” played no role at all, not even a rhetorical one, in Allied conduct of the war.) By the time the first American soldier set foot on the European continent most of the Jews the Nazis were going to murder had already been murdered. And of course, the notion that it was “America” that won the war is a bit tendentious. Great Britain and her Empire had been fighting (really, losing) the war for more than two years before the reluctant entrance of the United States into the war, and by far the greatest bulk of casualties taken by Hitler’s armies were inflicted by Stalin’s Red Army. The great battles that broke the Wehrmacht’s offensive potential and doomed Nazi Germany took place around Stalingrad and Kursk and took place well before D-Day. As Norman Davies points out it is simplistic, indeed really rather wrong, to depict the Second World War as one which the good guys simply “won.” It would be more if not entirely accurate to describe the European war as one in which a horrible tyranny went to war with another horrible tyranny and in the end, a horrible tyranny won.

Well, enough historical carping. Nazi Germany went down in flames, Hitler shot himself in his bunker, and the United States did play a role in these historical events, and what is more the United States did play a postwar role in rebuilding and securing the continent, such that if you were a Western European who survived the war you could then indeed look forward to an era of peace and unprecedented prosperity, enjoying civil liberties under variants of parliamentary democratic government. (Sorry, Eastern Europe, but at least your grandchildren would have something to look forward to. Sorry also Portugal, Spain, and Greece, but things would work out in the end. Until they didn’t.) In the United States internally the war probably had important cultural and social consequences. The cruelty and destructiveness (and failure!) of an anti-Semitic and racist regime did a lot to discredit anti-Semitism and racism, and the war itself brought large numbers of both women and racial minorities into the economic life of the nation in ways that they hadn’t been before, so the war experience did help lay foundations for a more egalitarian social order in the U.S. than existed before. So the story that the good guys won isn’t completely wrong — it’s at least tethered to reality at certain points. And the story is convincing enough that even the Germans, though they have understandable complaints about the destruction of their cities and their civilian inhabitants by bombing, would even say the “right” side won. After all the destruction and carnage, people in the United States and Europe might very well say things like “While there was terrible suffering, by the grace of God the right side won in the end. The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” And they will then all feel that their lives, and the universe, all have lots and lots of meaning.

American Patriotism, World ה

Call the world we actually live in, the world this post is written in, the world where there’s a Marshall Plan and something called Band of Brothers on HBO World Dalet. There is a world with different history called World He (not “he” but the name of the letter — see above)..

In World He things take a different turn from World Dalit when a minor member of the German Uranverein circulates a letter among top Nazi leaders in 1939 as a consequence of which Hitler’s regime undertakes a much more serious atomic research program than it did in World Dalit. As a consequence of the program, Nazi Germany has a working atomic bomb by mid-1943. This weapon is first used in a tactical role in Operational Citadel in 1943. The destructive power of the weapon allow German forces to smash through Soviet lines on both sides of the Kursk salient, allowing for the destruction of a huge part of the Red Army right in the middle of the Eastern Front. Moscow and Leningrad are subsequently incinerated with additional atomic bombs, and German forces begin sweeping toward their Arkhangelsk-Astrakhan line the marked their original Eastern front objective. What’s left of the Soviet government and army retreat to the Ural mountains. The German armed forces begin transferring units back to Western Europe. Between these additional forces and atomic weapons, any possible invasion of the European continent by British and American forces is now completely infeasible. Furthermore, Britain is now exposed to the possibility of atomic destruction. While Winston Churchill is determined to continue fighting the war no matter what the cost pretty much no one else in United Kingdom is. Churchill is removed from the premiership by a vote of his war cabinet and secret negotiations are begun with Germany for an armistice.

Under the terrible pressure of losing a war which by this point he expected to be winning, President Roosevelt dies of a stroke in December 1943. He is succeeded by Vice President Henry Wallace, who vows that the United States will continue the global struggle against tyranny. The U.S.-German war goes as a bitter trans-Atlantic stalemate for some months until the Kriegsmarine succeeds in launching a specially-modified A4 rocket from a U-boat at the East Coast of the U.S. This weapon is not very accurate — experts disagree as to whether it was aimed at either New York or Philadelphia. It misses both and hits (and thoroughly destroys) Princeton, New Jersey. Hundreds of thousands of people in the New York-New Jersey area are sickened, many fatally, by the subsequent fallout.

In a speech before the Reichstag in Berlin, Hitler formulates a peace proposal, suggesting that if the United States would lay down arms and “eliminate the influence on its politics of International Jewry” that the two nations could live at peace — the same sort of peace Hitler has just concluded with the British Empire. President Wallace angrily rejects this proposal and vows to fight on. But by this point many Americans are either disgusted or frightened by the war, seeing no reason to go on fighting in Europe when they have clearly already lost. A peace movement, calling itself the “George Washington Party” (did not President Washington warn us of the dangers of foreign entanglements?) convinces General Douglas MacArthur to resign his commission and run for President in the 1944 election. MacArthur, running on a peace platform, trounces President Wallace.

The German position at this point is tricky. There are hardliners in the Nazi movement who want to to use the German monopoly in atomic weapons to utterly destroy the United States, but ultimately a more pragmatic policy, urged on Hitler by the likes of Albert Speer, wins out. Speer notes that the United States is still fighting Japan in the Pacific War, and a U.S. victory there will represent a victory of the white races over the yellow ones. Furthermore, German resources are spread fairly thin as they attempt to digest their vast conquests in what used to be the Soviet Union. So eventually U.S. negotiators get a surprisingly good deal out of their German counterparts. The German Reich will allow the United States to remain intact and at peace, as long as the United States is willing make certain changes in its society that will prevent world peace from ever being threatened again. In 1946, President MacArthur and Chancellor Hitler meet in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, shake hands, and sign the Treaty of Paris, hailed by many commenters as a masterpiece of statesmanship that will be the foundation of peace and prosperity for decades to come.

(Subsequent historians speculate on Hitler’s sincerity in signing the Treaty of Paris, and some think that Hitler intended to conquer or perhaps annihilate America eventually when the opportunity presented itself. But Hitler’s own health was poor at this point and he dies in his bed at at the Berghof in 1948. His successors have their hands full with the project of subduing and administering their enormous East European empire — a task that proves far more difficult than they had anticipated. Eventually they settle into a modus vivendi with the United States. With Germany as the world’s dominant power in any event, they find this arrangement satisfactory in any event.)

In order to help implement these changes, a small corps of German experts arrive shortly after the signing of the Treaty of Paris. The Amerikahilfamt is headed by Baldur von Schirach, an inspired choice for, although a dedicated Nazi (he was the former Gauleiter of Vienna) he is also half-American and descended on his mother’s side from two signers of the Declaration of Independence. His operation is scarcely like an invasion; the Germans only occupy certain high offices and are able to find many able Americans more than willing to answer the call for the reconstruction of their country. Even the National Resettlement Office, advised by a highly energetic and competent technocrat named Adolf Eichmann, is able to recruit a capable and mostly American staff. Under the rest of the administrator of President MacArthur, and the subsequent one of President Joseph McCarthy and President Richard Nixon, various restructurings and reforms of American society are carried out. The reconstruction is much needed, as the subsequent war against Japan drags on into 1947, ending only with the brutal invasion of the Japanese home islands.

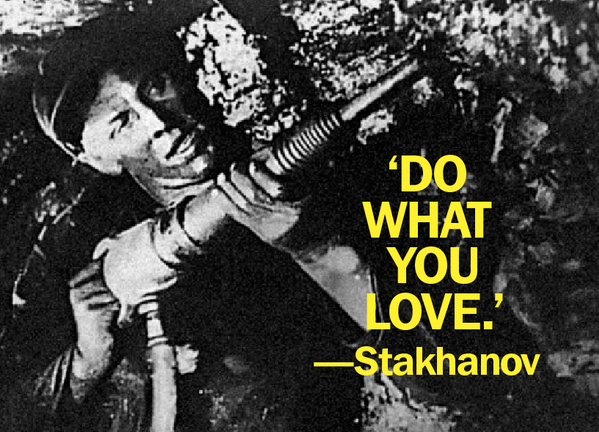

Thus did World He diverge from World Dalet. the children of World He learn a very different history in school, even the part of it up to 1939 where objective events were no different from that in World Dalet. The Civil War is an act of Northern Aggression against a peaceful society, and the Confederates are treated as tragic heroes defending the proper racial order, crushed under irresistible force by cruel, depraved fanatics. Their history books stress the horrors of the nineteenth century industrial system and the endemic and violent class conflict and poverty that existed in the United States’s Gilded Age. The gangster violence of 1920s is played up for all it is worth, while the culture of Jazz Age America is depicted as decadent and vile — this is blamed on Jews and black people. The subsequent suffering of the Great Depression and the World War are almost entirely blamed on Jewish financiers. “It’s a good thing the Germans won,” some people say, “or those Jews might still be in charge.”

The ethnic order of World He America is rather different form that of World Dalit America. Under a program begun under President MacArthur, initially as an emergency measure to provide labor to clean up atomic fallout in the northeast, African-Americans (note that the term “African-Americans” is unknown in World He; people use “Negroes” when they are being polite) were conscripted into a National Custodial Labor Program. This program was later made permanent and universal, “both for the good of America and America’s Negroes,” as President MacArthur would later explain, and that’s now the consensus opinion of anyone who matters that President MacArthur was right. To be sure, harsh measures were needed at first to deal with some resisters and troublemakers, but white Americans have a long tradition of applying harsh measures to African-Americans who won’t behave like white Americans think they should, so this turned out to be easy to do. With the defeat of Japan in 1947 and with the later Latin American counterinsurgency conducted under President Nixon a large number of Japanese and Latinos have subsequently been incorporated into the National Custodial Labor Program, where they are put to work in America’s thriving agricultural and extractive industries, which are such an important part of the 21st Century world’s prosperity.

As for Jewish people? Well, they don’t seem to be around any more as visible human beings. Someone’s great-grandmother might remember them. “There was a Jewish family that used to live on this street. The Leibowitzes, I think they were called. They seemed like nice people, in spite of all the nasty things people say about the Jews. They had to give up their house when they were resettled in 1949. I can’t remember where it was they were supposed to have been sent to. Paraguay, I think it was. Or was it Madagascar? Some people say Siberia. Well, in any event, I’m sure they’re doing fine.” But aside from someone’s great-grandmother, no one in World He America thinks about the Jews, save as abstractions in history books.

Yes, life is a bit different in World He America. There have been legal changes. Two new Constitutional amendments have been ratified: the 22nd, which repeals the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments and establishes the legal basis for the National Custodial Labor Program, and the 23rd, which limits the franchise to property-owning white men with at least six years of service in the United States armed forces. Schoolchildren are taught the importance of the latter amendment — the horrible events of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are taken to show that broadly-based democracy is a failure based on fallacies: the right to participate in government should be limited to responsible people with a stake in society who have demonstrated their patriotism. And civil liberties aren’t quite what they once were, but people like this because they think it makes the streets safe to walk at night when the police have a free hand to deal with criminals.

But things are not bad at all in World He America, if you’re one of the people who really matters. The world is peaceful and prosperous once again. In school children work hard on their lessons, especially on German. If they do really well they might win scholarships to the great universities at Göttingen or Heidelberg or the Technische Universität Dresden, a sure ticket to great success. But even those of more modest abilities can look forward to stable and prosperous lives that even their grandparents would not have known. There’s a Volkswagen in every driveway (that doesn’t have a BMW or a Mercedes, that is) and on the wall of most American living rooms you can find a Grundig High Definition Television on which families can watch the latest broadcasts from Berlin and Bayreuth. Better off families can get properly-trained, respectful servants who know their place through the Domestic Service of the National Custodial Labor Program. It’s a good present, and people look forward to an even better future.

And Americans look around the world they helped to make and are prone to say things like “While there was terrible suffering, by the grace of God the right side won in the end. The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” They feel proud to be a part of this, and feel their lives and the universe are suffused with meaning.