The concept of consent is a rock upon which decency is founded, at least so right-thinking people today believe. In medical ethics, for example, informed consent is considered absolutely necessary both for therapies and for participation in medical research. The Nuremberg Code, codified for the purpose of dealing with Nazi doctors in the aftermath of the Second World War, requires consent of subjects in medical research absolutely. If you have consent, you might be conducting bona fideresearch. Without it, you’re committing crimes against humanity, no ifs ands or buts. And consent is the core of decent sexual ethics as well. If from your partner you have it, if you affirmatively and enthusiastically have it, then good for you! And if you don’t have it, you’re a rapist.

Two subsidiary principles are important to the notion of consent: First, it must be obtained affirmatively. mere submission, acquiescence, failure to protest, and so on, do not constitute obtaining consent. Second, consent may be withdrawn at any time. In medical experiments this right to withdraw consent is implicit in the right of a subject to withdraw if ve believes continuation to be impossible. In sexual ethics it means that if your partner expresses a desire for you to stop doing what you’re doing, then you need to stop, no questions asked.

Defenders of consent speak of creating a “consent culture” and I’m certainly sympathetic to them; and alternative to a consent culture is without doubt profoundly unpalatable. But if we had a culture really based on consent, some interesting results would seem to obtain.

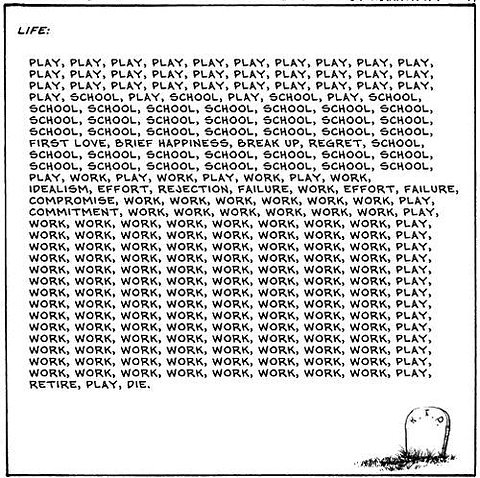

Consider: life itself is an experiment, and potentially one far worse than any medical experiment, or any sexual experience (or at least, potentially as bad, since in the process of being alive necessarily includes all the horrible things that can happen to you in medical practice or in sex, as well as far, far else besides). But it is impossible to obtain anyone’s consent to be brought into existence. And that would seem to indicate that if we had a consent culture, we should be antinatalists, indeed, very hard antinatalists if we take the core ethical notion of our consent culture at all seriously.

Likewise, just as in a consent culture we would necessarily have the right to withdraw from an experiment if we find it impossible to go on, and the right to withdraw from sex at any time and for any reason (or indeed, for no reason), then we surely have the right to walk away from life if we no longer consent to being alive. The right to turn down the deal on offer, to walk away from that we find repugnant, is as fundamental to our liberty and our autonomy as anything could be. A real consent culture would be pro-suicide choice.

It is no defense that life contains some good things. The Nazi doctors on trial at Nuremberg would not have gotten off if they had somehow conveyed benefits on their experimental subjects, and in a consent you’re not allowed to have sex with someone who can’t consent (say, a minor or an incompetent person). You’re still a rapist even if the person you had sex with wasn’t harmed, even if they enjoyed it.

Perhaps there’s some fancy intellectual dancing that can distinguish between subjecting people to life without their consent and other, more narrow fields in which consent is seen as somehow necessary. I don’t think so, though.